Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

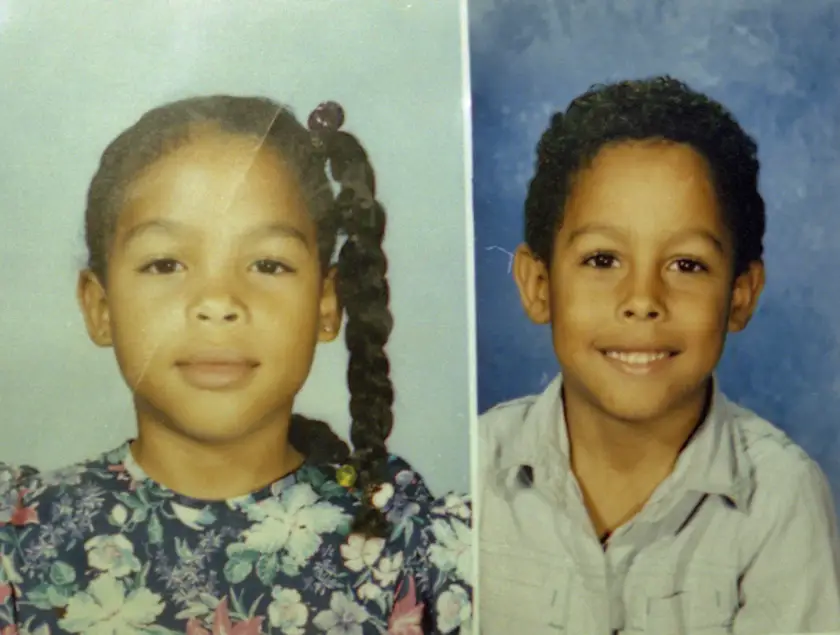

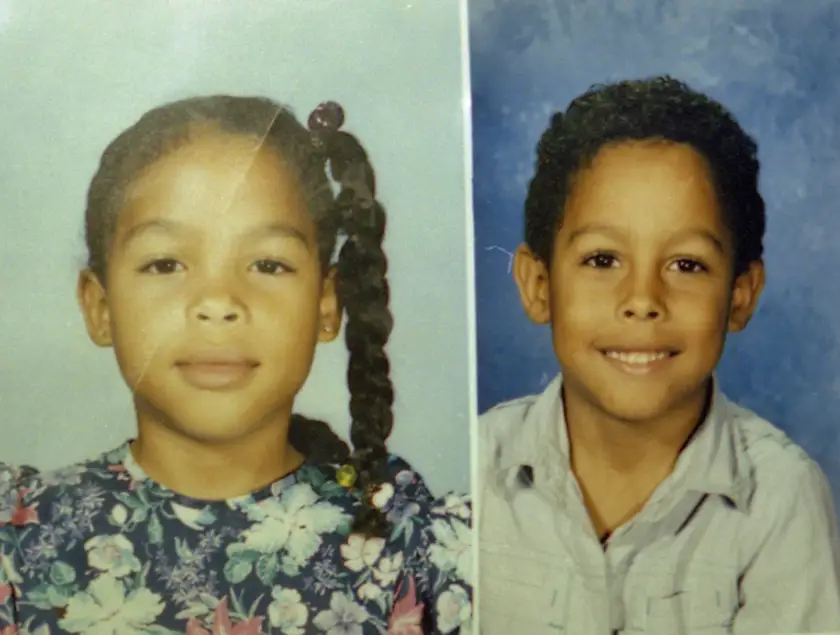

The 1999 case of siblings Curtis Jones (age 12) and Catherine Jones (age 13) from Florida

I can’t even imagine the unimaginable suffering and hell that 12-year-old Curtis Jones and his 13-year-old sister Catherine endured.These young siblings were sexually abused for years by a relative, their desperate pleas for help ignored by the very system meant to protect them. Feeling trapped and abandoned, they committed a tragic act in 1999—killing their father’s girlfriend, whom they believed was enabling the abuse.In a heartbreaking injustice, they became the youngest children in U.S. history to be charged as adults with first-degree murder.

Catherine’s parents met in Palo Alto, California, when her mother, 17-year-old Stacie Parks, served 23-year-old Curtis Jones Sr. at a Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant. Their relationship began despite Parks’ family objecting to an interracial relationship between a white girl and a Black man.

The violence started almost immediately. According to Parks’ sworn affidavit, Curtis Jones started hitting her within a month of dating, and he hit her while pregnant, causing a tear in her uterus. Parks blamed this injury for Catherine’s premature birth—the baby weighed just 3 pounds, 11 ounces and was nicknamed “Munchie.”

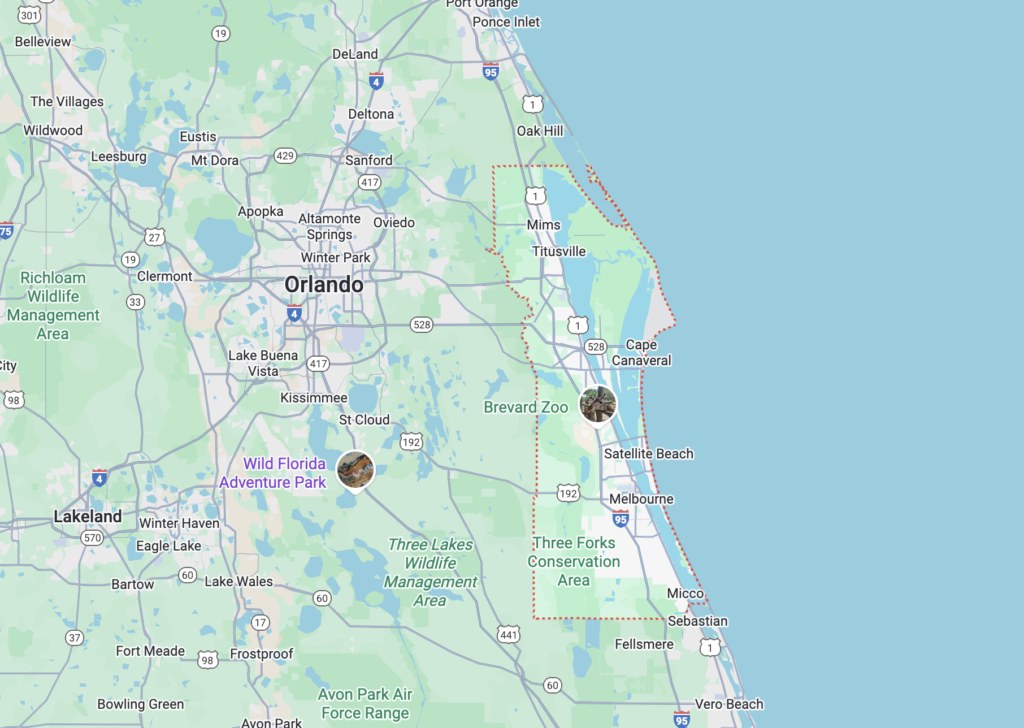

Less than a year later, on May 31, 1986, Parks gave birth to Curtis in Alabama, where the couple had moved before eventually settling in Brevard County, Florida.

The violence in the household wasn’t limited to domestic abuse. Their father was charged with second-degree murder after shooting two men in a Titusville pool hall in 1989 when Catherine was 4 years old. The charge was later reduced to a misdemeanor when police decided it was self-defense.

The violence continued, and Parks said she left many times, but Jones would convince her to return. They eventually married in 1989, only months before Parks would leave for good. She pawned a gold chain to pay for a one-way ticket to her mother’s home in Kansas.

But there was a heartbreaking complication: “My mom said I couldn’t bring the kids because they were biracial,” said Parks, who also said she feared her husband’s revenge if she took Catherine and Curtis.

Catherine was 4 years old. Curtis was 3.

In 1993, Parks made a desperate attempt to save her children. Parks drove to Brevard and took them from school to Kansas without permission. According to court records, she was arrested for third-degree felony of “interference with custody.” The children were returned to Florida, and charges were dropped.

Catherine and Curtis were sent back to their father—and to the abuse that awaited them.

After their mother left, a male relative came to live with the family in Port St. John. This person’s background should have been a massive red flag. The family member once spent six years in prison in Alabama for strong-arm robbery. In 1993, he was arrested and later convicted of having sex with a 14-year-old girl.

Despite this conviction for sexually assaulting a minor, this person was allowed to live in the home with two vulnerable children. Even more disturbing: that family member, convicted in 1993 of sexually assaulting his girlfriend’s daughter, lived in the house in Port St. John with the children and even shared a room with the boy.

Curtis, a young boy, was forced to share a bedroom with a convicted child molester.

The abuse Catherine endured was severe and ongoing. “He would make me perform oral sex to the point where I would throw up,” Catherine told reporters in 2009, adding that her father and his girlfriend, Speights, did not believe her.

Catherine Jones had told her brother about how a male relative had pleasured himself while watching her shower. The abuse was constant, violating, and inescapable.

Curtis was also being victimized, but Catherine didn’t know initially. The moment when they discovered they were both victims is heartbreaking: Catherine never knew Curtis was also being sexually abused until one day, while walking to Space Coast Middle School, he told her that he believed her story—because it was happening to him as well.

They were just children—12 and 13 years old—sharing the unbearable knowledge that they were both being abused, and no one would help them.

A few years earlier, the state looked into claims that the same family member had molested them. During a visit to his mother, 8-year-old Curtis said he was being molested by their relative.

The result: Nothing. The investigation was closed.

A third investigation occurred in 1996 when Curtis had a bruised and swollen eye. This was clear evidence of physical abuse.

The result: Nothing. Officials did nothing.

This is perhaps the most damning failure. Less than four months before 13-year-old Catherine Jones and her 12-year-old brother, Curtis, shot and killed their father’s girlfriend in 1999, child welfare investigators found signs that they were being sexually abused by a family member.

State investigators conducted physical examinations and identified physical indicators of abuse and sexual molestation during examinations of the children.

The result: After each investigation, officials did nothing, according to reports obtained by FLORIDA TODAY.

In confidential documents revealed to Florida Today by an attorney working to gain the children clemency several years ago, it was revealed that the Department of Children and Families said there were indications of abuse but did nothing.

When Catherine told her father and his girlfriend about the abuse, they didn’t believe her. “He didn’t believe me at that time, and it felt like he was taking sides, like he chose his relative over me,” she said. “I expected him to be at the point where he would want to kill him.”

Catherine later explained why the state’s failures were so devastating: “Their only avenue was to take the kids out of the household, but you can’t tell a kid something like that, especially us,” Catherine said. “One of our parents had already left.”

They had already been abandoned by their mother. The thought of being taken from their father—despite everything—was terrifying.

No one believed her, Catherine said, except her 12-year-old brother. They had only each other.

Feeling completely abandoned by every adult and system that should have protected them, the children began to plan. That was the year the duo hatched a plot to kill a male relative they claimed had been sexually abusing them. They planned to kill their father and his girlfriend, Sonya Nicole Speights, because they felt their cries for help were being ignored.

The plan was comprehensive—they intended to kill all three people they held responsible: the abuser, their father who didn’t believe them, and Speights who also dismissed their claims.

They stole their father’s .380-caliber semiautomatic handgun.

On January 6, 1999, the children found themselves home alone with Sonya Nicole Speights. In this coastal community, the sky seemed limitless—young dreamers only had to tilt their heads to the heavens to watch the rockets launched from Cape Canaveral. Speights was doing a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle at the dining room table when Catherine used his 9mm handgun to shoot her in the torso.

The siblings started by shooting Speights with their father’s handgun, hitting her four times out of nine bullets fired. Catherine fired the shots, and Curtis Jones assisted by handing the weapon to his sister.

They immediately realized their tragic blunder, tried to cover up the crime and ran to a neighbor’s house to say it was an accident. Catherine later acknowledged that killing Speights was a tragic mistake—it should have been the abuser, not her.

After shooting her, they panicked and ran off into woods near their Port St. John home, where they were apprehended the following morning.

Curtis, facing prison at 12, asked his attorney if he could bring his Nintendo.

Catherine Jones and Curtis Fairchild Jones became the youngest murder defendants in the United States to face trial as adults. Prosecutors charged them with first-degree murder, meaning they faced potential life sentences.

When the crime first occurred, police, attorneys and newspapers reported the children killed the girlfriend because they were jealous of attention their father was giving her. This simple jealousy narrative dominated initial coverage.

Facing life in prison, the children and their attorneys made a critical decision. They never mentioned the abuse to their attorneys and pleaded guilty to second-degree murder, accepting the sentence of 18 years and probation for life. Catherine Jones was 13; Curtis was 12.

There was no trial. Because of the plea deal arrangement, there was no trial or testimony and thus no opportunity for Curtis and Catherine, and their attorneys, to show the documentation from the agency which would later be renamed the Department of Children and Families.

The evidence of years of sexual abuse, the multiple investigations, the system’s failures—none of it was presented in court.

“It is somewhat haunting to me that there was a world of horrors that this child was growing up in that was never explored,” said Curtis Jones’ attorney Alan Landman.

Curtis entered prison at age 12 in 1999—two years before Xbox was released. Curtis missed out on the various incarnations of the PlayStation consoles. With no cable television in the state prisons, it’s safe to assume he’s never watched a single episode of Family Guy or SpongeBob Squarepants, both of which debuted in 1999.

The Hurricane Escape (2004): Curtis had another year added to his sentence when a hurricane knocked down a prison fence and he was among a group of inmates who ran in 2004. He was caught 24 hours later, adding 318 days to his sentence.

His Transformation: Curtis’ visitors over the years have included his father, his mother Stacie Parks, a cousin, his grandmother and a few personal friends. According to the DOC, he has not been disciplined for any rule infractions since 2008. Curtis is now an ordained minister.

Physical Changes: Now 29 years old and sporting a couple of prison tattoos—a panther on his left arm and the word “Mob” on his stomach—Curtis Jones leaves prison an ordained minister.

Catherine’s experience was different but equally isolating. In a 2009 interview, she revealed something stunning about prison: “At one point I was just so happy to be away,” Catherine said. “I know that sounds, like, really messed up, but there was a point where I was just away from all that and I was by myself and I was safe.”

Prison felt safer than home.

Finding Love: Senior Chief Ramous K. Fleming of the U.S. Navy began writing Catherine after reading her story several years ago. He started visiting her and after cupid struck, the couple married on Nov. 27, 2013, in the chapel at the Hernando Correctional Institution.

It has been 10 years since Catherine and Curtis Jones killed their father’s girlfriend and became the youngest in the country at the time charged with first-degree murder as adults. FLORIDA TODAY reached out to them, hoping they would tell the story that was never heard in court because of a plea deal that sent them each to prison for 18 years. Catherine Jones agreed. Her brother did not.

Reporter John A. Torres’s investigation revealed the full scope of what had happened to these children. The confidential DCF documents obtained showed multiple investigations, clear evidence of abuse, and systemic failure at every level.

Florida Today reported that Jones was released at 7 a.m. from the South Bay Correctional Facility, which is south of Lake Okeechobee. He was 29 years old.

What He Faced: Jones, who did not want to comment for this story, has never had to cook his own meals, shop for his own clothes, balance a checkbook, look for a job, send out a resume, hunt for an apartment, pick a cellphone plan, buy furniture, learn to drive or figure out how to take public transportation.

He had been released with a $50 debit card, a bus ticket, and lifetime probation.

If calculations for “gain time” or “good behavior” are correct, Catherine will leave prison on July 28, as a 30-year-old married woman who has never driven a car, texted on a cellphone, walked a high school hallway, gone on a job interview, attended a dance or surfed the Internet.

She wrote in a letter: “After spending all of my teenage years and most of my young adulthood behind bars, I’m being released into a foreign society so different from what I left behind. Of course there are fears, mainly because there’s so much I must learn to function like a normal person: how to drive, fill out job applications, text, dress for a job interview”.

It’s crucial to remember: No one had to die in this case. Speights’ own children had to grow up without a mother. Sonya Nicole Speights was 29 years old when she died, doing a jigsaw puzzle on an ordinary Wednesday. Her death was a tragedy that could have been prevented if the system had worked.

“The story of siblings Catherine Jones and Curtis Fairchild is a tragic tale of several people and systems that failed these two young victims before dumping them in prison,” said Ashley Nellis, senior research analyst with the Sentencing Project.

Parks said she is closer with Curtis than Catherine, but hopes to rebuild that relationship. “I never asked why they did this,” Parks said. “I figured I knew why. They had grown up with violence their whole life.”