Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Souad : Burned Alive: A Victim of the Law of Men (published in 2003),

In a small, dusty village on the West Bank during the late 1970s, a young girl named Souad was born into a world where being female meant a life of shadows and silence. Her family, devout Muslims bound by ancient traditions, lived under the iron rule of her father, a stern shepherd who saw his daughters as little more than burdens—.

workers to tend the goats, clean the home, and marry off quickly to preserve the family’s honor. Boys were kings; girls were disposable. Souad recalls how her father beat her and her sisters relentlessly for the smallest infractions, like speaking out of turn or not working fast enough. She witnessed horrors: rumors of baby girls being smothered at birth if they weren’t sons, and one of her sisters strangled by their father with a telephone cord for some perceived shame, her body buried secretly in the night

Honor was everything—a fragile thing guarded by blood if necessary. Souad grew up fearing marriage, knowing it often meant trading one tyrant for another, but she dreamed of love, a forbidden spark in her oppressive life. As Souad entered her late teens, around 17 or 18, that spark ignited. She caught the eye of a neighbor, a young man named Faiez, who whispered promises of marriage during stolen moments in the fields. In her village, sex before marriage was a death sentence, especially for women, but Souad, starved for affection, gave in to the brief affair. It was her first taste of tenderness, but it came at a terrible price—she became pregnant. Terror gripped her as her belly swelled in secret. She hid it under loose clothes, but whispers spread. Her family discovered the truth, and in their eyes, she had stained their honor beyond repair. To them, she was no longer a daughter but a curse that needed to be erased. Honor killings were whispered about in the village—women drowned, strangled, or burned for far less. Souad’s parents convened in hushed tones, deciding her fate: she must die, and it would be done quietly by a family member to “cleanse” the shame.

One fateful afternoon, as Souad, heavily pregnant, bent over a basin washing clothes in the courtyard, her brother-in-law Hussein approached. He was the one chosen for the task, a man she had known her whole life. Without a word, he doused her from head to toe in gasoline, the fumes choking her as she begged for mercy. Then, with a match, he set her ablaze. Flames erupted across her body like a demon unleashed, searing her skin, melting her clothes into her flesh. She screamed, rolling on the ground in agony, but no one came to help—her family watched from afar, ensuring the job was done. The pain was unimaginable: her skin bubbled and charred, waves of fire ripping through every nerve, from her face down to her legs. She felt her hair singe away, her eyes blur with smoke, and the world spin into blackness. Over 70% of her body—some accounts say up to 90%—was burned, leaving raw, weeping wounds that exposed muscle and bone. She should have died there, but somehow, amid the torment, her will to live flickered on.

Villagers heard her cries and carried her scorched body to a nearby hospital, but even there, mercy was scarce. In the West Bank, victims of honor crimes were often left to suffer, seen as deserving their fate. Doctors provided minimal care—basic bandages, painkillers when available—but infections raged through her open wounds. Souad describes the pain as endless torture: every movement felt like knives twisting in her flesh, the burns itching and throbbing day and night, her skin cracking and peeling in sheets. She lay in that bed for weeks, delirious with fever, her pregnant belly a constant reminder of the life inside her fighting too. Miraculously, amid the haze of agony, she gave birth to her first child—a son she named Marouan. Holding him was a bittersweet anchor; he was the product of her “sin,” but also her reason to endure. The hospital staff, wary of her family’s influence, kept her isolated, but word of her plight reached a compassionate European aid worker named Jacqueline Thibault from the Swiss NGO Terre des Hommes.

Jacqueline saw Souad’s suffering and knew staying meant certain death—her family would finish the job if she survived. In a daring rescue, coordinated with the Red Cross, Jacqueline smuggled Souad and baby Marouan out of the hospital under the cover of night. They were hidden in safe houses, papers forged, and flown to Switzerland, a land as foreign to Souad as another planet. The journey was fraught: Souad, bandaged and weak, endured bumpy rides and tense checkpoints, her burns screaming with every jolt. In Switzerland, she arrived broken but alive, undergoing dozens of surgeries to graft skin, reduce scarring, and ease the chronic pain that would haunt her for life. The cold alpine air was a shock after the desert heat, and learning French felt impossible at first, but with therapy and support from social workers, she began to heal—not just her body, but her shattered spirit. Flashbacks tormented her, nightmares of flames and betrayal, but she pushed forward for Marouan, watching him grow from a frail infant into a healthy boy in this new world of freedom.

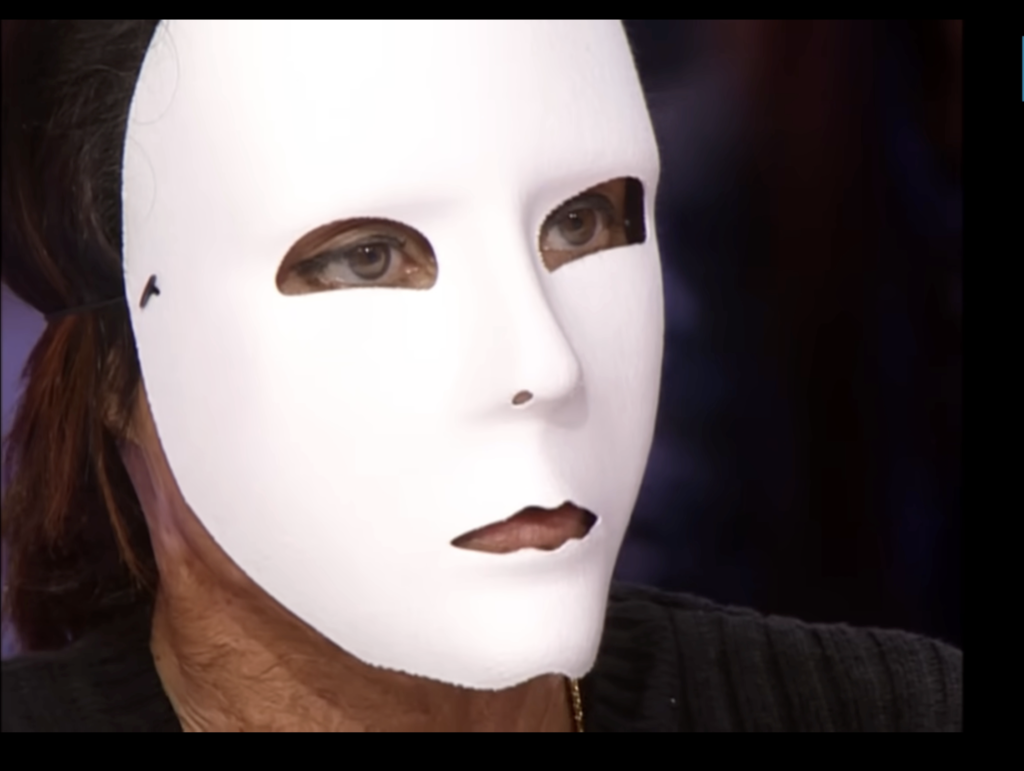

Years passed, and Souad rebuilt her life in anonymity, fearing her family’s reach even across oceans. She married a kind man who understood her scars, both visible and hidden, and together they had two more children—daughters she raised with the love and equality she never knew. Her family grew to three kids in total: Marouan, her firstborn from the affair that nearly killed her, and the two girls born in safety. Life in Europe brought challenges—cultural clashes, language barriers, ongoing medical treatments for her burns—but also joys: education for her children, simple freedoms like walking unveiled, and the chance to advocate. Through repressed memory therapy, Souad unlocked buried traumas and penned her story, Burned Alive, to shine a light on honor violence and inspire other women. Her journey from a village girl doomed to die to a survivor raising a family in peace is a testament to resilience, though debates linger about the details—critics point to inconsistencies in her account, like medical improbabilities and timeline errors, suggesting parts may be exaggerated or fictionalized. Yet, in her words, it’s a cry for change, proving that even from ashes, life can rise.