Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In 1965, a girl was born into a nomadic family in the harsh Somali desert near Galkayo. Her parents named her Waris—which means “desert flower”—one of twelve children in a family that wandered with their goats and camels, never knowing if tomorrow would bring water or drought, life or death.

Little Waris lived barefoot, tending animals under the scorching sun. There were no schools, no hospitals, just endless sand and sky. She was free in the vastness of the desert, running wild with her siblings, learning to survive on almost nothing.

But at age four, something terrible happened. Her cousin raped her. In that culture, a violated girl brought shame to her family. The solution was brutal: at five years old, Waris was held down—by her own beloved mother—while a village woman used a dirty razor blade to mutilate her genitals.

She describes it in haunting detail: being blindfolded, feeling the cutting of the most sensitive part of her body with no anesthesia. She fainted from the pain, felt herself leaving her body. The woman scraped away her external organs, then stitched her vagina almost completely shut, leaving only tiny openings. This is called infibulation—the most extreme form of female genital mutilation.

Dirie was forced to endure excruciating pain and both short- and long-term complications. The procedure caused her to take ten minutes just to urinate and ten days to menstruate. At five years old, she swore to herself that one day she would fight this practice—she just didn’t know how yet.

Years passed. Waris grew up herding her father’s goats, dreaming of a different life. Then, at thirteen, her father made an announcement that shattered her world: he had arranged her marriage to a sixty-year-old man. The price? Five camels.

“That’s the best kind,” her father told her cheerfully. “He’s too old to run around. He’s not going to leave you.”

Waris looked at the old man limping with his cane and knew this would not be her fate. That night, she whispered to her mother: “I’m going to run away.”

Her mother woke her before dawn. In the dim light, they embraced, tears streaming down both their faces. “Be careful,” her mother whispered. “And Waris… please, one thing. Don’t forget me.”

“I won’t, Mama.”

Then Waris ran into the darkness, alone, crossing the dangerous Somali desert on foot. She had no shoes, no map, no money—just desperate hope. She walked for weeks until she reached Mogadishu, the beautiful port city with white buildings and palm trees that seemed like another world.

Through a stroke of luck, Waris’s aunt in Mogadishu connected her with an uncle who had just been appointed Somalia’s ambassador to Britain. She traveled to London—but not as family. She became their housemaid in a four-story mansion, working endlessly while barely understanding English.

When her uncle’s term ended in 1983 and the family returned to Somalia, eighteen-year-old Waris found herself alone in London with no visa, no money, nowhere to sleep. She had nothing. She slept at the YMCA and took a job cleaning toilets at McDonald’s, struggling to survive in a foreign land.

One day, while working at McDonald’s, a photographer named Terence Donovan spotted her. He saw something extraordinary in this tall, graceful African woman. The photos he took launched her career.

Within years, Waris Dirie transformed from a refugee cleaning toilets to walking the runways of Paris, Milan, and New York. She appeared in campaigns for Chanel, Revlon, and L’Oréal. She was the first black woman to appear in an Oil of Olay advertisement. In 1987, she graced the exclusive Pirelli Calendar and even appeared as a Bond girl in “The Living Daylights.”

The desert nomad who once had nothing was now a world-famous supermodel, traveling the globe, wearing designer clothes, living the dream.

Yet behind the glamorous façade, Waris carried her trauma. The FGM had never healed properly. Eventually, she underwent surgery to reverse some of the damage—a painful but liberating procedure that finally allowed her body to function normally. She explained how amazing it felt to urinate in less than ten minutes and menstruate in less than ten days.

For years, she remained silent about what had happened to her, like millions of other women. In that world of fashion and beauty, who would want to hear about such horror?

Then, in 1996, at the height of her career, Waris Dirie did something revolutionary. She gave an interview to Marie Claire magazine and told the truth about female genital mutilation. She became the first high-profile woman to speak publicly about this practice.

The response was overwhelming. Her story appeared on shows like 20/20. In 1997, the United Nations appointed her as a Special Ambassador for the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation.

In 1998, she published her autobiography, “Desert Flower: The Extraordinary Journey of a Desert Nomad.” The book became an international bestseller, translated into dozens of languages, touching millions of hearts. People wept reading about the little girl in the desert, the escape, the transformation, and her courage to speak.

Waris didn’t stop at telling her story. In 2002, she founded the Desert Flower Foundation in Vienna, dedicating her life to ending FGM. She traveled the world, speaking before governments, opening schools and medical centers.

The foundation helped launch treatment centers in Berlin, Amsterdam, Stockholm, and Paris to provide care to FGM victims. She addressed EU ministers in Brussels, appeared on Al Jazeera—the first person to discuss FGM on an Arab television channel, reaching 200 million viewers.

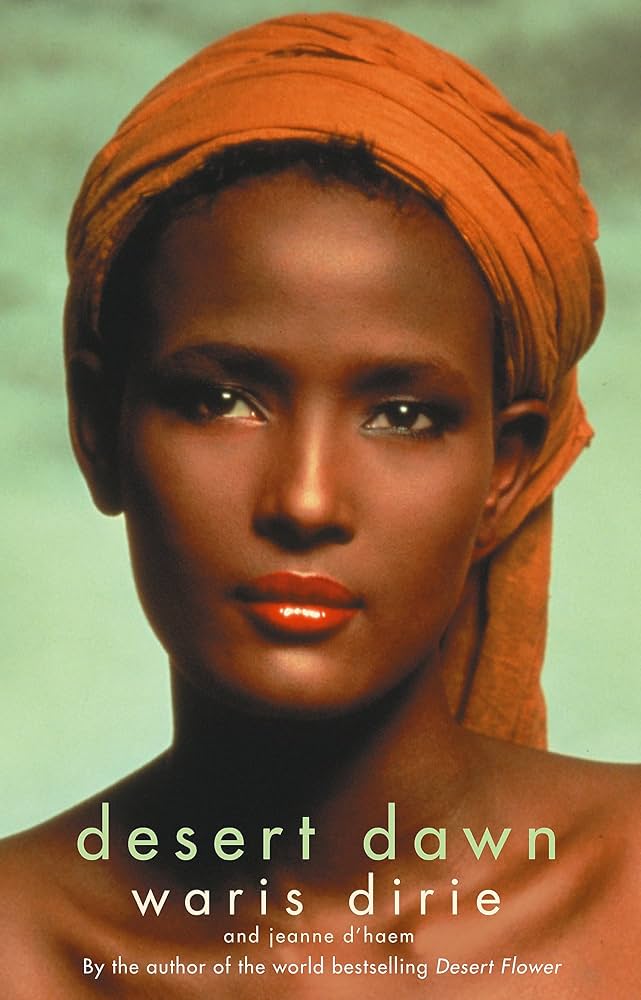

She wrote more books: “Desert Dawn,” “Desert Children,” sharing more of her journey and educating the world. In 2009, her life story became a feature film, also called “Desert Flower,” bringing her message to even wider audiences. In 2020, her story was adapted into a musical.

The statistics are staggering: over 200 million women and girls alive today have experienced FGM. Every 11 seconds, another girl undergoes this procedure. It happens in 92 countries across Africa, the Middle East, and Asia—and increasingly in Europe and North America due to immigration.

Waris received death threats from fundamentalists who viewed her activism as an attack on their culture. But she never stopped. She received the Legion of Honour from France, the World Social Award from Mikhail Gorbachev, and countless other honors.

From a barefoot nomad girl with no future, to a woman who changed the conversation about women’s rights worldwide—this is Waris Dirie’s transformation. She turned her deepest trauma into her greatest purpose.

She reflects: “Apart from the circumcision — and the attempted forced marriage by my father, selling me to a man who could have been my grandfather for five camels — I would not want to change my childhood”. She cherishes both worlds she’s known: the freedom of the desert and the opportunities of the modern world.

Her name—Waris, “desert flower”—proved prophetic. As she once said: “I think it fits me because I have survived through a lot in my lifetime, and this flower is well known for that. It can sustain in the mountain and the desert. It can survive and bloom at the same time”.

Today, because of her courage, laws have changed, girls have been saved, and millions of people understand that FGM is not culture—it’s violence. The little girl who ran through the desert alone, terrified but determined, grew into a woman who gave voice to the voiceless and hope to millions.

That is the story of Waris Dirie—a true desert flower who bloomed against all odds.